Well-Tested Tools and Techniques Needed for Tight Times

By Dr. Ben S. Graham, Jr.Chairman

The Ben Graham Corporation

© Copyright 2010, The Ben Graham Corporation. All rights reserved.

Links may be established to this paper.

It never hurts to get back to the basics, but in the tight times we are experiencing today it can be especially beneficial. One of those basics is Process Improvement using the tried and proven methods of ‘Work Simplification’. Work Simplification grew out of the outstanding work of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth who were improving work processes a century ago. It is defined as, “The organized application of common sense to eliminate waste and develop more efficient and effective ways of doing work”. Common sense is as relevant today as it has ever been and the tools that we use to organize the facts for applying that common sense have been and continue to be updated.

Work Simplification applied to work processes starts with preparing detailed charts of major processes. These charts show (step by step) the processing of each of the parts (in manufacturing processes) and documents, both electronic and hard copy (in all processes). Then teams of the most experienced people who do that specific work are coached in how to creatively improve the process - and they do it. The process is re-charted as they think it should be, the changes are presented to management for approval and those changes that are approved are installed. The normal outcome is that a number of steps (sometimes large portions of a process) are eliminated and a few things are added that make the process more effective. The net result is doing less work and accomplishing more.

Defining a Project

A potential process improvement project is easily defined. This is done by listing the process name, the name of the lowest ranking manager whose authority spans the entire process, the start and end point of the process, the organizational units/departments that are involved and any specific objective for the project (other than simply improving it) such as adapting it to be in compliance with changed regulations, reducing the processing time or making the process less error prone, etc. Once the major processes of the organization have been so defined they are presented to senior management who select those they would like to do first. For those, additional information is added including the names of the team members, a start date, a finish date (when recommendations will be presented to management) and the name of a facilitator who will draw the charts and guide the team.The ‘As – Is’ Charts

As soon as a project becomes active, a chart is prepared of the process as it is currently being performed. It usually takes a facilitator (who has worked with detailed process charts) only a day or two to prepare the chart. Then the team meets, usually for one to two hours, at a time least likely to interfere with their regular work. They study this ‘As – Is’ chart step by step. During their first meeting the team is organized with a team leader (usually someone with considerable experience whose work is central to the process being studied) and a recorder who will keep a list of the change ideas that the team comes up with. This meeting also, usually, includes some coaching in how to find improvements.

Improvement Coaching

The improvement coaching, which the team members receive is basically questioning the process step by step. The questioning involves asking each of the five descriptive questions (what, where, when, who and how) along with the judgment question, why. What are we doing at this step and why are we doing it? Where do we do this step and why do we do it there? When do we do it and why do we do it then? Who does it and why does that person do it? And, how do we do it and why do we do it that way?

The most important aspect of this questioning is the sequence in which the questions are asked. We always ask the questions “What – Why?” first. If those questions don’t produce a reasonable answer there is not (in the eyes of the people who are most knowledgeable about the process) a good reason to continue doing that work. That part of the process should be eliminated and the rest of the questions are superfluous. When we eliminate a portion of the work we produce the greatest benefit that we can with the least cost. Failure to ask this question first invites wasting time on alternative ways of doing something that shouldn’t be done at all.

If, however, there is a good reason for doing that step we continue with the questions “Where – Why?”, “When – Why?” and “Who – Why?” These questions lead to opportunities for changing the location, the timing and the person doing the work. These are changes that generate improvement with little cost. There is no need for new equipment or developing a new method at this point. We continue to do the work as we have been doing it, however, in a better place, and/or at a better time and/or by a more appropriate person.

The questions, “How do we do it and why do we do it that way?” should not be pursued until after the other questions have been asked and answered to the satisfaction of the team. These questions lead to changes in method and equipment. All too often process improvement is initiated at this detailed level of ‘How’, which invites unfortunate outcomes such as programming expensive new equipment to perform unnecessary work in an inappropriate place, at an awkward time and by an inappropriate person.

Re-Charting

As the team comes up with ideas for changing it the ‘As – Is’ chart, it is revised with little more difficulty than writers have in revising their writing on a word processor. After a couple of passes through the chart by a team of experienced employees they arrive at a ‘To – Be’ chart. Since these two charts are drawn using lines and symbols using the same software, they can be precisely reconciled, quickly and easily. The differences become the list of changes that the team will recommend to management. Those that are approved will be installed and the ‘To – Be’ chart is easily revised to reverse the changes involving recommendations which were rejected.

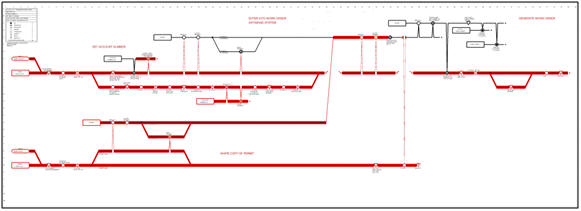

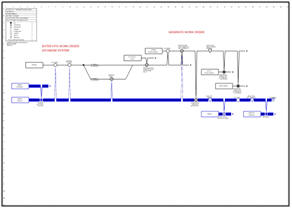

When the recommendations are being presented to management for approval, the ‘As – Is’ chart and the ‘To – Be’ chart are prominently displayed, usually one above the other so that the difference in size becomes apparent. The ‘To – Be’ chart is usually considerably shorter and contains fewer steps. We encourage facilitators to color in the lines of those portions of the ‘As – Is’ chart that have been eliminated in red and color in the portions of the ‘To – Be’ chart that they have added in blue. This provides a clear illustration of the differences between the two charts. (It is imperative, for the integrity of this display that these two charts be printed in the same scale.)

AS-IS

TO-BE

A bird’s-eye view of charts from an actual project.

Presenting the Recommendations

The meeting at which the recommendations are presented for management’s approval generally last about an hour. The participants are the team members and the mangers of the areas through which the process flows. It is co-chaired by the team leader and the manager who is the lowest ranking manager in the company whose authority spans the entire process. Normally he is the highest ranking manager attending the meeting. Since the team is made up of one person from each of the areas affected by the process and there will be one manager at the meeting from each area, there will usually be about the same number of team members as there are managers. To help set a productive tone for the meeting it is important for the team members and the managers to sit together with alternate seating rather than sitting in two groups facing each other. This can be achieved easily by having the team members arrive a little early and take alternate seats.

The meeting begins with the senior manager covering an agenda as follows; team members read their proposal, managers question the individual recommendations and the team members fill in details to answer the questions and then the senior manager works with the other manager, one recommendation at a time to decide whether to approve, reject or assign to a specific manager to work on it further, usually with a time frame of no more than five days. (If after the five days that manager is still not satisfied, that recommendation will be rejected rather than to hold up the implementation of those recommendations which have been approved.)

The actual reading of the proposal is done by the team members starting with the team leader who gives the bottom line of benefits that their changes will produce if they are all accepted. Then each recommendation is read by the tem member whose work area is most heavily affected by the change. This gives considerable credibility to the ideas because the people who are reading the recommendations have been chosen as those who have the best current experience of that portion of the process. This reading usually takes two or three minutes.

Then the managers ask questions and this portion of the meeting is when the mangers usually become sold on the changes. They find themselves asking questions of the people who actually do the work and who have been carefully studying that work for several days. Essentially, we have a normal situation of people who do not do the work, but are knowledgeable and involved with higher level responsibilities, asking questions of those who actually do it.

After, usually less than an hour of questioning the senior manager takes over the meeting for decisions. Many times I have been told you will never get the managers in our organization to decide on anything the first time they hear about it. However, I have been doing this for half a century and have yet to see it not happen. And, when it happens the reasons are obvious. The changes make clear sense. They are also beneath the responsibilities of the people who have to decide. And, the only reason they haven’t been made already is because they have interdepartmental impact. The work simplification approach has gotten us past these limitations.

Implementation

Once these decisions have been made the team has a list of approved changes. This list is then reviewed by the team, one recommendation at a time to determine the activities required to implement the approved changes. Activities will involve changes in forms, equipment, policies, written procedures, computer programs, facilities and work places, with each approved recommendation usually requiring several of these. And, there is one more activity that will be required for every approved change – training. As Confucius put it roughly twenty-five hundred years ago, “To expect performance without proper advisement is ridiculous.” The team carefully works through these options using a spread sheet and produces a list of activities for implementation. This usually takes less than an hour. These activities are then assigned and a network chart may be prepared to help think through the sequencing of this work.

As the teams complete one project after another the effectiveness of the organization steadily improves. Simultaneously, the people who have served on the teams and seen their ideas put into practice generally share a well deserved sense of pride in their accomplishments.

There is, however, a most important caution. As the teams discover parts of the processes that can be eliminated they must be assured that it is work that is being eliminated and not jobs. This can be accommodated by increasing output which provides more for sale without a corresponding increase in costs. This in turn permits reducing price and increasing sales, a win – win situation for company and customer. Simultaneously, some reduction in staff may be accomplished, without layoff, through normal attrition and transferring duties. However, it simply does not work to expect people to work creatively and enthusiastically on teams to eliminate their jobs or the jobs of their co-workers.

SummaryProcess Improvement using the techniques of Participative Work Simplification is a quick and effective way of getting more work and better work done with less effort. Those executives who can earn the trust of their people can free those people up to use their ingenuity to find and implement changes, many of which are only visible to them, building an organization that is as efficient and effective as the combined experience and ingenuity of their people can make it.

Dr. Ben Graham is an industrial engineer (a fellow of the Institute of Industrial Engineers) with 50 years experience in the tools of his profession, mostly specializing in process improvement. He worked with many of the leaders of the profession including six years with Dr. Lillian Gilbreth, twenty-five years with Alan Mogensen (the creator of Work Simplification) and with his father, also Ben Graham, who adapted work simplification from factory operations to information processing. Early in his career it became apparent to him that the engineering aspects of work improvement were straightforward when compared with the human aspects, so he pursued and completed doctoral work in behavioral science. His doctorate was awarded with distinction. His company introduced Graham Process Mapping Software in 1990.