Allan Mogensen and his Legacy

By Dr. Ben S. GrahamChairman

The Ben Graham Corporation

© Copyright 2008, The Ben Graham Corporation. All rights reserved.

Links may be established to this paper.

I was recently asked if I could provide some insight into the work improvement contributions of Cornell graduate, Allan Mogensen. I worked with him as did my father, Ben S. Graham Sr. who, coincidently, started at Cornell before leaving to serve in the military during WWI.

Art Spinanger and my father, Ben S Graham, Sr. met at Mogensen’s Work Simplification Conference in 1944. This was a six week program that was held at Lake Placid, New York. The two men are shown in the Class of 1944 group photo (they happened to be sitting side by side in the center of the middle row – my father is in the center with the only woman at the conference to his left and Art Spinanger to his right.)

Both men made excellent use of the materials learned at the conference. Art built the “Deliberate Methods Change” program at Procter and Gamble which gradually grew to produce billions in savings as indicated by the October 1984 issue of “The National Productivity Report” displayed in the following illustration. My father took the Process Charting that was presented at the conference and expanded it from the single flow used to chart the manufacturing of a part in a factory to multiple flow needed for charting information flow.

Art’s program at Procter and Gamble grew steadily and one of the truly remarkable things about it was that it was still going strong forty years after Art attended Mogy’s Conference (as indicated by the National Productivity Report).

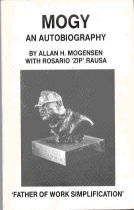

I knew Art well. He was a thoroughly decent man. I can’t remember him ever raising his voice but when he spoke people listened. I served with him on the board of a group called the “Improvement Institute” which was made up primarily of graduates of Mogensen’s Conferences. And he was an early recipient of that organization’s highest award, the Mogensen Bronze (An illustration of the Mogensen Bronze appears on the cover of Mogensen's autobiography, “Mogy”, and is shown in the next illustration.)

Art kept himself in good shape. He was a very good tennis player and continued to play competitively in older age groups. In his last years he retired to Arizona. Shortly before his death, the president of Procter and Gamble flew out to Arizona to visit him and thank him for his outstanding contribution to the company. I am sorry that I do not remember the man’s name but I heard about it and know that Art was most pleased by it.

My father worked for the Standard Register Company, manufacturers of business forms. He took the single flow process chart that he learned at Mogy’s conference and expanded it to chart the multiple documents used in a typical information procedure. (i.e. the requisition, purchase order, receiving ticket, warehouse locator tag, accounts payable voucher and check, etc. – that all might be a part of a procurement process.) His initial purpose was to provide the information needed to design better forms. This proved very effective and before long Mogy invited my father to join the staff of his Lake Placid Conferences. Then in 1953 my father began conducting Paperwork Simplification Conferences on his own, while continuing to serve on Mogy’s staff. Lillian Gilbreth, who also served on Mogy’s staff at Lake Placid, did the same at my father’s conferences.

Unfortunately, my father died in January of 1960. He had conducted 21 public conferences and a number of private, in-house conferences by that time and I had worked with him during his last years. Shortly after his death Lillian called to say, “Of course, you are going to continue your father’s work. What can I do to help?” I was a young man of twenty-eight at the time with little thought of rising to such a challenge but the way Lillian put it to me was hard to resist. She coached me as I prepared for my first conference and attended all of them that I conducted for the next six years. I am proud to say that since then we have steadily adapted the work to accommodate the increasing automation of information processing and almost a half century later we are still conducting them. I am also pleased to say that I joined Mogy, on his staff, at his workshops at Lake Placid and Sea Island that he continued until close to his death.

The people who attended Mogy’s workshop pumped billions of dollars worth of productivity improvement into their companies and our economy. “Mogy” is an autobiography prepared by Mogy with the help of Zip Rausa. It was funded by the Improvement Institute. The cover photo is the Mogensen Bronze, which was … “awarded periodically by the Improvement Institute to an individual who has been a leader in productivity improvement and has sustained outstanding accomplishments at the National or International level.” In the bronze, Mogy’s head is thrust forward as it often was in real life. Mogy was a very dynamic man.

Mogy often told a story from his early career. He had graduated from Cornell, then taught for a while at the University of Rochester and then went out on his own as a consultant. He was working at the Remington Arms Co. when he was approached by a foreman who told him that he had been making guns all of his life. What the hell would a young college professor have to tell him about making guns? Mogy didn’t argue. He assured the foreman that he didn’t know anything about making guns but he knew how to study work. He was going to chart the flow of each of the parts of a gun and then he could study that flow step by step and find opportunities for improvement. He showed the foreman a flow process chart, briefly explained it and then asked him to make one. They selected a part, which was a spring in the bolt of a bolt action rifle and the foreman agreed to prepare the chart. About two weeks later, Mogy returned to Remington, approached the foreman and asked him if he had made the chart. The foreman told him he had made the chart and found some dumb stupid things they we’re correcting, and by the way were already charting the rest of the parts.

It was this experience and others like it that led him to the conclusion that “…the person actually doing a job probably knows more about that job than anyone else and is therefore the one person best suited to improve it.” This became a fundamental of his Work Simplification Conferences. The following (in italics) is the preface that I wrote in 1989 for Mogy’s autobiography (Mogy passed away later that year.)

I first met Allan Mogensen when I was a teenager, while my father was attending his Work Simplification Conference at Lake Placid New York in 1944. I recall him as a dynamic man, usually in the center of a discussion or racing about in his grey Mercedes.

I didn’t see him again for years but I heard of him often. My father was a member of Mogy’s staff each summer at Lake Placid and later, when my father started his Paperwork Simplification Conferences, Mogy participated in them.

I next saw him in 1962. My father had died in 1960 and I was continuing his work. I was conducting a workshop in Quebec when Mogy called asking to visit. He flew up in his Navion and after observing a few sessions invited me to become a member of his Lake Placid staff as my father had been. Thus began a relationship which has been extremely fulfilling.

I rode with him in his Mercedes and his Navion. I listened to him deliver fiery presentations to rapt audiences and I joined him in discussions with workers and with senior executives. And I found that, even if he was simply walking from one meeting to another at a convention, he exuded enthusiasm.

What he was like as a young man and what happened to him that has kept him so fired up are outlined in the pages that follow. As you read them keep in mind that the man you are reading about was still running the socks off people half his age when he was in his eighties. And, you may also want to keep in mind that a good deal of the prosperity we all enjoy today is here because of Mogy and others inspired by him and in turn by them.

When Mogy’s career began, dramatic increases were occurring in our American productivity. Frederick Taylor had introduced careful scientific analysis of work. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth increased the effectiveness of this analysis enormously with an astounding assortment of analytical techniques which enabled people to increase their output with reduced effort.

Reactions to scientific management varied and did not fall into orderly predictable groups. Some owners and managers pursued it with zeal and others refused to consider it. Some labor groups perceived the new efforts as exploitive. Others tried them and liked them. Meanwhile, the new profession of industrial engineering was in its early years, a profession destined to bring to the world previously unimaginable prosperity while reducing human misery. (The first industrial engineering classes were offered at Penn State in 1908.) The industrial engineers worked to utilize the resources of nature and human nature for the benefit of mankind and they got results. Output increased while effort decreased, often with little or no increased investment. Profits increased making it easy to increase wages and salaries and dividends for stockholders. Reduced unit costs enabled companies to lower their prices, passing on benefits to customers.

As productivity increased Americans found themselves soaring to dizzying heights. The national mood was “every day in every way we are getting better and better.” Herbert Hoover, an industrial engineer of hard-working Quaker heritage was in the White House. He understood what was happening and he supported it. Why not study and learn and improve and be better off?

But, many people were not studying and learning and improving. People who had never engineered an improvement in their lives found prosperity and without understanding why it was happening they bet on a better future. They thought they could get on an ‘easy street’ being built by others. This book is about building ‘easy street’ and one of the key men who did it.

The purpose of this preamble is not to argue politics. Rather it is to introduce the story of a man who became caught up in the beginnings of an improvement process which shared the benefits with everyone involved, owners, managers, employees and customers.

Mogy experienced the excitement of the awakening of scientific management. He lived through one economic situation after another, boom and bust, world conflict, recession, inflation. Through them all he did not lose sight of the essential formula for success. Nor did he jump on the management bandwagons as one panacea after another became the darling of industry and disappeared as fast as it arose.

Mogy was in touch with fundamentals and the more he worked with them and understood them, the more steadfast became his belief in them. He is as superbly confident today as he was in the twenties because he has seen the process work, first hand. He has tasted it, lived it, and known it. And, he has enjoyed the rich feeling of passing on confidence to thousands of others, many of whom enthusiastically attest to how Mogy changed their lives.

Along the way he found that when the techniques of work improvement were applied they often produced resistance sufficient to kill the process. Since he knew the problem was not in the techniques, he did not question them. Instead he got at the resistance in a much more direct and innovative way. He gave the techniques to the would-be resisters and let them see the benefits for themselves and share in the excitement of creating the improvements. Note the example in Chapter two with the foreman at Remington Arms. This was his unique contribution and distinguished work simplification from most work improvement efforts. When he left Factory magazine to become a consultant to industry he refined this formula.

By 1937 he had the process well enough organized to begin his Work Simplification Conferences. Each year he carefully introduced a small number of people to rigorous training and over the years hundreds carried a message back to their companies. Some accomplished little, many returned the cost of their training quickly and easily and some revolutionized companies with previously unimaginable productivity gains.

As the years passed Mogy and his work have been discovered and

rediscovered many times. An impressive list of authors, Erwin Schell,

Douglas McGregor, Peter Drucker, Ren Lickert, Chris Argyris, Warren Bennis,

and recently Tom Peters and Bob Waterman have come across his handiwork.

The last two found quite an alumni group from Mogensen’s Work

Simplification Conferences in the companies they termed excellent.

During this time the merit of Mogy’s work has also been recognized by

several professional societies. Today three impressive awards are given

periodically to outstanding leaders in the field of productivity

improvement. They are the Taylor Key of the Society for the Advancement of

Management, The Gilbreth Medal of the American Society of Mechanical

Engineers and the Mogensen Bronze of the Improvement Institute. Only two

people have received more than one of these. Art Spinanger, a Mogensen

student, 1944 who built the Procter and Gamble program (see Chapter 12)

has received the Taylor Key and the Mogensen Bronze. Mogy alone has

received all three.

Ben S. Graham, Jr.

February 19891985 Recipient of the Mogensen Bronze

More recently I have had a couple of occasions to meet with Tom Peters and on one of these we chatted about Mogy. Actually Tom lit up when I mentioned Mogy. Then he told me this story.

He had been invited back to Cornell, also his alma mater, to make a presentation. I think it was something like reunion weekend. While he was speaking he got some rather rough heckling and it didn’t let up. With a bit of concern he pressed on and then he noticed a white haired elderly fellow stand up, work his way out of his seat-row, walk down the aisle, climb up on the stage and head towards him. All this time he had been pressing on. Then the elderly gentleman got to center stage, took the mike and said, “My name is Allan Mogensen and I’ve been doing this work for 50 years and I’m telling you, what this young fellow is saying is right.” That was how Tom first met Mogy. (The phrase in quotes is as I remember it. The number 50 may have been a little different).

Summary

There have been thousands of major contributions to our nation’s productivity and, in turn, to our standard of living. None, to my knowledge, have exceeded those of Allan H. Mogensen who devoted his life to introducing work simplification skills into as many organizations as he could and pushing those skills down in those organizations to the people who did the work. It was an honor and a pleasure to know him and work with him.

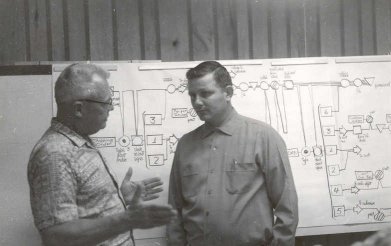

Allan Mogensen (left) with Ben S Graham, Jr. at an early 1960s conference.

Dr. Ben S. Graham, Jr., is the Chairman of the Ben Graham Corporation. His company pioneered the field of business process improvement, and has provided process improvement consulting, coaching and education services to organizations across North America since 1953. He has helped thousands of people make sense of their business processes through his firm, his courses, his lectures and his writings. He holds four university degrees; B.A. (with Phi Beta Kappa), B.F.A., M.B.A. and Ph.D. (awarded with distinction).

The Ben Graham Corporation publishes Graham Process Mapping Software, which is designed specifically for preparing detail process maps. More information about the software is available at http://www.processchart.com